Love For Many Wrong Reasons: Three Years After The Cathedral’s Fire, A Look Back At Victor Hugo’s Passion For Notre Dame

(ANALYSIS) The famous Victor Hugo novel that English readers know as “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” was originally published in 1831 in French under the title “Notre-Dame de Paris”. By Wednesday morning, April 17, 2019, two days after the appalling fire in the cathedral, five different versions of the novel had soared into the first, third, fifth, seventh and eighth places on Amazon France’s bestseller list.

The book and its popularization in films and cartoons have greatly shaped our perceptions, and the story of Quasimodo and Notre Dame is one of many stories that have become part of our collective worldview.

For that reason alone, how and why Victor Hugo portrayed the cathedral are worth a close look.

Why did Hugo love Notre Dame?

When I too went looking for “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” the day after the fire, I read it for the first time since I was 15 years old. This time through, I marveled at the creative genius embodied in Hugo’s unique characters and how they intermingled in his tragic — albeit melodramatic — plot, while at the same time trying to understand exactly why he loved the cathedral so much.

Most people don’t realize Hugo wrote “Notre-Dame de Paris” in large part because he championed Gothic as the quintessential French architecture style. He wanted to make his countrymen aware of the treasures of Gothic architecture that were being lost in France — and particularly in Paris.

Many Catholics like myself are devoted to Our Lady, and we love the cathedral at least partly because of its dedication to the Mother of God. French-speakers think of the church simply as Our Lady because that’s what Notre Dame means. The centuries-long patronage of the city of Paris is also clear in the full name of the cathedral, Notre-Dame de Paris, and until recent times, Feb. 15 was celebrated as the Feast of Our Lady of Paris.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:

On the site now occupied by the courtyards of Notre-Dame de Paris there was as early as the sixth century a church of Notre-Dame, which had as patrons the Blessed Virgin, St. Stephen, and St. Germain. … On the site of the present sacristy there was also a church dedicated to St. Stephen. The Norman invasions destroyed Notre-Dame, but St-Etienne [French for St. Stephen] remained standing, and for a time served as the cathedral. At the end of the ninth century Notre-Dame was rebuilt, and the two churches continued to exist side by side until the eleventh century when St-Etienne fell to ruin. Maurice de Sully resolved to erect a magnificent cathedral on the ruins of St-Etienne and the site of Notre-Dame.

When Maurice de Sully, Bishop of Paris, with the support of King Louis VII, began to construct Notre Dame in 1162 in the newly emerging, quintessentially French, Gothic architectural style, the goal was to create a cathedral worthy of the cultural capital of France, for the glory of God and the glory of his holy mother.

Hugo was a freethinker, so his reasons for loving Notre Dame were purely secular ones. More about that later. But first some relevant background.

Why the book was once on the ‘Index’

In 1834, three years after its publication, “Notre-Dame de Paris” was placed on the Catholic Church’s “Index of Prohibited Books”. It wasn’t removed from the index until 1959 — the index was later discontinued by Pope Paul VI in 1966. One source said the book was condemned with other books that were anti-clerical, blasphemous or heretical. Another source asserted that the book was placed on the index not for any theological reason — although the book undeniably has strong anti-clerical and anti-Catholic aspects we’ll look at later — but rather because the book was "sensual, libidinous or lascivious."

Most modern readers are blasé about the distinct raciness of the plot. Maybe that is because more people are familiar with the Disney animated version, which sanitizes many aspects of the story.

In Hugo’s novel, Esmeralda is a barely 16-year-old girl who is thought to be a gypsy because she was raised by gypsies. But she was actually born from an encounter between an unknown man and a poor French prostitute named Paquette from Reims, who had prayed to the Blessed Virgin for a child to love. It’s one of many examples in the novel in which superstitious self-seeking prayers are made by immoral characters — prayers that are left unanswered or answered in unexpectedly disappointing ways. Paquette had her baby girl baptized as Agnes.

At 1, Agnes is stolen by gypsies and replaced with a one-eyed, bow-legged, seemingly feral boy with a severely crooked back. He is about four years old, with a face neither his unknown mother nor Paquette could love. The changeling is exorcised by the local bishop and sent to Paris, to a foundling cradle in Notre Dame Cathedral, where unwanted children are dropped off in hopes someone will take them. A young priest at the cathedral, the fanatically studious Claude Frollo, fosters the child.

Even though the Disney movie claims that Frollo gives Quasimodo a “mean name,” meaning half formed, Hugo left it to the reader to decide. He wrote that the priest found the child on Quasimodo Sunday and “called him Quasimodo; whether it was that he chose thereby to commemorate the day when he had found him, or that he meant to mark by that name how incomplete and imperfectly molded the poor little creature was.”

Quasimodo Sunday is the Sunday following Easter. The name is taken from the first words of the traditional Latin entrance hymn of the day, “Quasi modo geniti infantes,” which reads in full, “Like newborn infants, desire the rational milk without guile, that thereby you may grow unto salvation: If so be you have tasted that the Lord is sweet.” Quasimodo does not mean half- or quasi-formed. It means something more like “as in the manner of.”

When Quasimodo is 14, he becomes the bell ringer of the cathedral. When he loses his hearing from swinging among the bells, that loss reduces his connection with the world — which already ostracizes him — even further.

After her child is stolen, Esmeralda’s mother, Paquette, eventually comes to live in a cramped and dank penitent’s cell that adjoins a Parisian square where criminals are executed. Not really “penitent,” she doesn’t bewail her own sins, but she endlessly bewails her loss and berates the gypsies, who she thinks ate her precious child in a satanic ritual. She curses at Esmeralda whenever the girl goes by because she believes the girl is one of the race of people who stole her child. It is not until almost the end of the novel when Esmeralda and her mother are briefly reunited and learn the truth about each other in a poignant scene. Soldiers who then come to drag Esmeralda away to execution for a trumped-up charge of witchcraft throw her mother aside from where she is clinging to her daughter, and Paquette dies from the impact of her head on stone stairs — which her daughter witnesses as a final horror just before she is put to death.

The distinct vein of raciness comes in because the plot of the novel is concentrated mostly on the passion of the main male characters for this barely 16-year-old girl. First among them is Claude Frollo, who is a priest, an archdeacon at Notre Dame and a crazed dabbler in black arts. There is also Pierre Gringoire, an addled philosophizing and penniless playwright whom Esmeralda “marries” for four years — having an ersatz wedding ceremony without consummation, only to save his life from hanging by the vagabonds of Paris. Phœbus de Châteaupers, a handsome, womanizing captain, is attracted to the girl in hopes of a casual fling. For Quasimodo, Esmeralda is precious, the unattainable love of his life.

Esmeralda dances and sings among the crowds in Paris for money. “Her voice, like her dancing and her beauty, was indefinable, something pure, amorous, aerial, winged, as it were.” She does not dance provocatively, but she is casually aware of how men respond to her beauty, and she deftly deflects male advances with a dagger. She has been told that she will find her mother one day only if she keeps her virtue.

But then she falls so madly in love with the handsome cad Phoebus, she is about to give herself to him — even after he makes it clear to her that he has no intention of marrying her — when the obsessed Frollo leaps from where he has been spying on them and stabs the captain in a fit of jealousy. And there’s more. You’ve gotten the idea.

As I said, it’s all quite melodramatic besides being pretty racy stuff. With its plot elements of the gypsies as baby stealers and grown men obsessed with a teenage girl and its attribution of half-human status to the “hunchback” — not to mention its melodramatic plot line — it’s unlikely that the novel could be published these days.

Another characteristic that would make this novel unpublishable today is one that it shares with many other classic novels, such as “War and Peace” and “Moby Dick”. In these books, and many like them, you find huge chunks of authorial musings on subjects that have nothing to do with the plot.

I remember during my last reading of “War and Peace” being struck by all the digressions into Tolstoy’s theory of human history and the “Russian soul” and his indictment of Napoleon for cowardice, among other things. And as one wag commented, reading “Moby Dick” prepares readers for the next time they need to cut up a whale. But somehow these books don’t sink with their heavy ballast of authorial opinionating; we skip over or forget the long digressions because the characters are so vividly realized and the stories are so riveting. The same applies to “Notre-Dame de Paris”.

View of Paris from the top of Notre Dame Cathedral. Stitched with Autopano, processed in CaptureOne. Photo by Pedro Szekely

Kings of Judah sculptures on the facade of Notre Dame Cathedral. Paris. restored by Viollet le Duc after their decapitation during French Revolution. Photo by Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez (Lmbuga)

Hugo, the freethinker champion of Gothic architecture

Victor Hugo was born in 1802 of an atheist father and a Catholic mother. In his youth, he was a royalist and a practicing Catholic, but he later became staunchly anti-royalist, anti-clericalist and anti-Catholic. First, he became a deist, dabbled in spiritualism, participated in séances and then became a pantheist toward the end of his life.

As I mentioned earlier, Hugo wrote “Notre-Dame de Paris” in his 20s in large part because he championed Gothic as the quintessential French architecture style.

Hugo dedicated the whole of Chapter 1 in Book 3 to the cathedral. He raged about the sad state of neglect, the damage done by revolutionaries, Huguenot iconoclasts and even renovators who imposed the latest styles on Notre Dame. He valued Notre Dame as a connoisseur, appreciating it as a glorious historic monument of irreplaceable importance to French culture.

Hugo wrote, “The Church of Notre-Dame at Paris is no doubt a sublime and majestic edifice. But notwithstanding the beauty which it has retained in old age, one cannot help feeling grief and indignation at the numberless injuries and mutilations which time and man have inflicted on the venerable structure.”

Hugo wrote the novel in the late 1820s, under the reign of King Louis Philippe, which followed after the French Revolution, the reign of Napoleon Bonaparte and the collapse of the First Empire.

Hugo set the book’s story around 350 years before his time, when Notre -Dame was already about 300 years old, during the reign of Louis XI, in the late Middle Ages. Formed by the beliefs of the post-revolutionary era in which he lived, Hugo painted the Middle Ages — in which French society was ruled by the king and the church — as superstitious, hypocritical, corrupt, brutal and heartless, very dark ages indeed.

Not-really-dark ages

Of course, the Middle Ages weren’t actually dark, as many like Hugo have painted them. To the contrary, as the religiously unaffiliated American author Henry Adams noted, “Four fifths of (man’s) greatest art was created in those supposedly dark days, to the honor of Jesus and Mary.” One of those great works of art was the cathedral of Notre Dame, the church that Hugo loved so much, in spite of his hatred of the Church with a capital C:

“The facade a vast symphony of stone … the colossal product of the combination of all the force of the age … a sort of human creation, mighty and fertile like the divine creation, from which it seems to have borrowed the twofold character of variety and eternity.

“Four fifths of (man’s) greatest art was created in those supposedly dark days, to the honor of Jesus and Mary."

“What we here said of the facade must be said of the whole church; and what we say of the cathedral of Paris must be said of all the churches of Christendom in the Middle Ages.”

A truly dark age

The era of the French Revolution, which began in 1789, was a time that can truly be called a dark age. Aside from the enormous slaughter and lawlessness of the Reign of Terror — during which the guillotine was used to execute at least 40,000 hapless souls who found themselves out of sync with the waves of enthusiasm that swept through the mobs from one day to the next — revolutionaries destroyed most of the country’s churches and monasteries.

For example, out of the 300 churches in Paris in the 16th century, only 97 were left standing in 1800. At some point, Notre Dame was taken over for use as a wine warehouse and marked for demolition.

Anti-Catholic revolutionaries continued the destruction that iconoclast Protestant Huguenots had started 200 years earlier. The French revolutionary government ordered the destruction of a 13th century statue of the Virgin Mary on the portal of the Virgin at the main entrance of Notre Dame. And some say the destroyers mistook the 28 statues of biblical kings of Judah in a row in the Gallery of the Kings on the façade for statues of French kings, which is why they beheaded them. One of Hugo’s complaints in Book 3 was, “Who has thrown down the two ranges of statues — who has left the niches empty?”

Architect Violett le Duc restored the heads, but no one knew until 1977 where the originals had gone. This article, “Heads of 13th Century Notre Dame Statues Discovered in Paris,” describes the recent discovery of the heads of 21 of these kings during work on the basement of the French Bank of Foreign Trade. Now the rediscovered heads are on display at Cluny Museum also known as the National Museum of the Middle Ages.

However, the destruction was not focused just on those kings because during the revolution, most if not all of the religious images in Notre Dame were destroyed along with symbols of royalty. All fleur-de-lis, symbols of royalty, were also removed by various means, including the chipping away of carvings and the painting over of fleur-de-lis in sections of stained glass.

How Victor Hugo helped save Notre Dame

When Hugo began his campaign to save Notre Dame and other Gothic masterpieces in stone, many of France’s remaining churches — including Notre Dame — were marked for demolition, with profiteers engaged in reselling the stones.

In an article titled “War to the Demolishers,” which Hugo wrote for the Review of the Two Worlds in 1823, Hugo declared war against the “massacre of ancient stones” and the “demolishers” of France's past.

“A universal cry must finally go up to call the new France to the aid of the old,” he said.

After that essay and after the huge later success in 1831 of his novel “Notre-Dame de Paris,” King Louis Philippe declared in 1844 that restoration of churches and other monuments would be a priority of his government. French Gothic architecture was officially recognized as a treasure of French culture. The post of Inspector of Historical Monuments was created, and under the inspectors’ direction, the first efforts to restore major Gothic monuments began. Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc won a competition to be hired to oversee the cathedral’s restoration in 1844, and le-Duc continued the work on his own after Lassus died in 1857.

Over the rest of the 19th century, all of the major Gothic cathedrals of France underwent extensive restoration, thanks in large part to Victor Hugo.

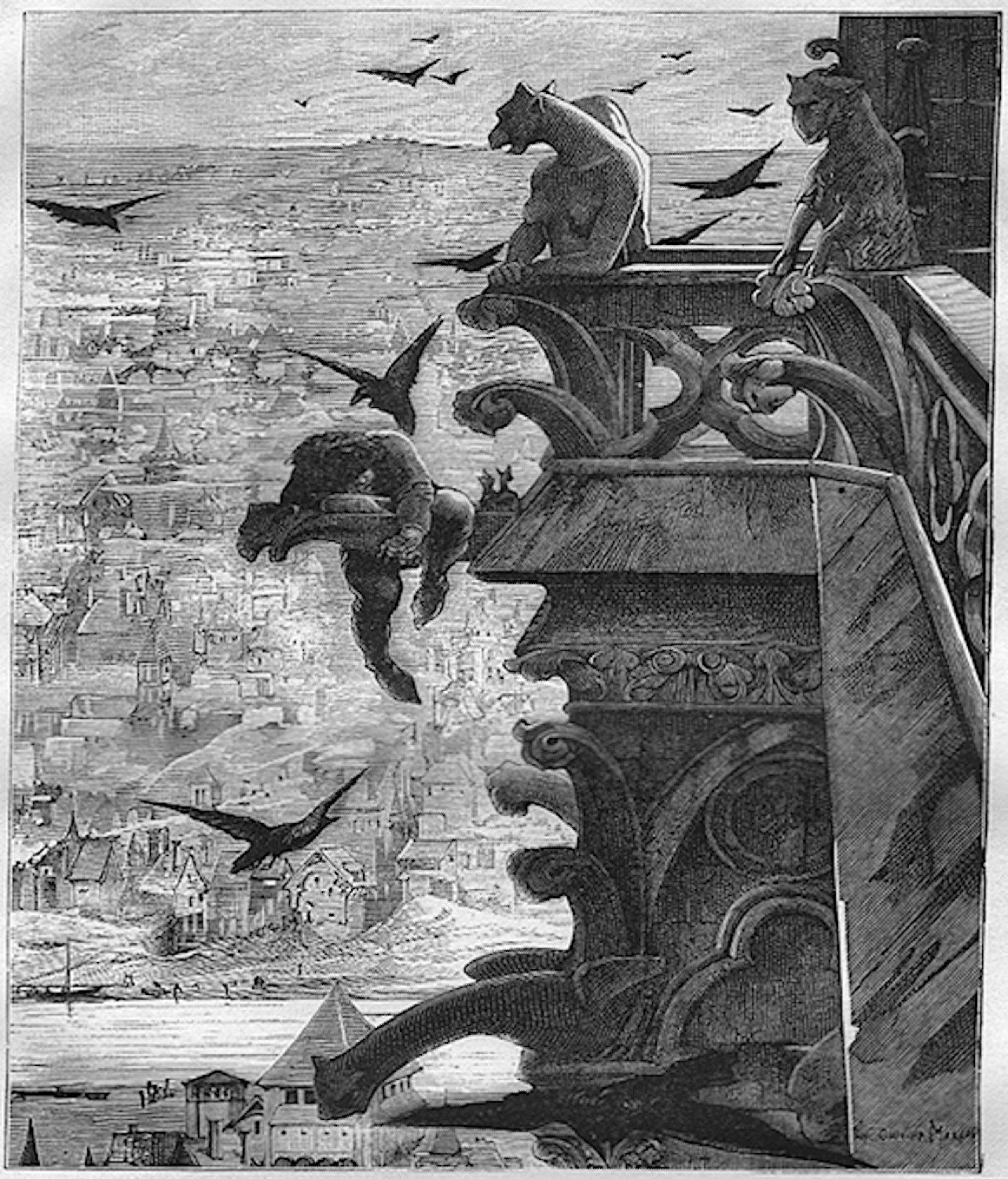

Cathedral is Hugo’s main character, made alive by Quasimodo

Although most people think of Quasimodo as the protagonist of the novel, for Hugo, the great cathedral itself is actually the main character.

And for Hugo, Quasimodo was Notre Dame’s soul. He wrote that the superstitious people of the city thought of Quasimodo as a demonic spirit who gave life to the cathedral and who left it empty when he died at the novel’s end:

Egypt would have taken him for the god of the temple; the Middle Ages believed him to be its demon; he was the soul of it. To such a point was he so, that to those who knew that Quasimodo once existed Notre-Dame now appears deserted, inanimate, dead. You feel that something wanting. This immense body is void; it is a skeleton; the spirit has departed; you see its place, and that is all. It is like a skull; the sockets of the eyes are still there, but the eyes themselves are gone.

This flamboyant characterization illustrates again how far Hugo was from the Catholic understanding of the function of a church building as a sacred space. Any Catholic cathedral, any church, is never empty because the Blessed Sacrament — the consecrated bread and wine, which we believe are the body and blood of Jesus Christ — is always reserved in a tabernacle, and so we believe the Lord is always there. We would never think any cathedral or church was dead, unless the Eucharist had been removed.

"Every day some old memory of France goes away with the stone on which it was written.”

Victor Hugo, in “War to the Demolishers” | Photo by Étienne Carjat, 1876

Read the full text of “War to the Demolishers” at Review of the Two Worlds →

Creative Commons photo by Lionel Allorge

History of the bells, bells, bells, bells of Notre Dame

Quasimodo is not portrayed in Hugo’s novel as having any religious feelings. His devotion is reserved for the girl Esmeralda, for the villainous priest, for his adopted father Archdeacon Claude Frollo and for the cathedral’s bells.

Before the revolution, Notre Dame had ten main bells in its north and south towers and others in the spire and within the roof. The revolutionary government demanded that metal works and gold and silver objects of all kinds be turned over as raw materials to be recast as cannons, cannon balls, pikes, guillotines and coins. After all the original bells were removed in 1781 and 1782, only the 1681 Emmanuel bell — whose name means God with us — was not sent to the foundry.

Removing and transporting those bells must have been a daunting undertaking. Emmanuel, the largest, weighs 13 tons; its clapper alone weighs 1,100 pounds, and the rest of the bells weighed between 2 and 3 tons each. Sources do not agree on the reasons why, but Emmanuel alone was spared and put into storage. After Napoleon returned the use of the cathedral to the Catholic Church with the Concordat of 1801, Emmanuel was remounted in the south tower.

So, at the time Hugo was writing toward the end of the 1820s, the only original bell in the cathedral was Emmanuel.

Because the novel is set in the time before the bells were looted, Hugo describes Quasimodo’s love for the original bells, whose names Hugo copied from a document written before the revolution. In the novel, Quasimodo loved one bell above all, the one named Marie, which was obviously named in homage to the Virgin Mary.:

What he loved above all else in the maternal edifice, that which aroused his soul, and made it open its poor wings, which it kept so miserably folded in its cavern, that which sometimes rendered him even happy, was the bells. ... It is true that their voice was the only one which he could still hear. On this score, the big bell was his beloved. It was she whom he preferred out of all that family of noisy girls which bustled above him, on festival days. This bell was named Marie.

The ending of the song “The Bells of Notre-Dame” that begins the Disney movie “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” captures the love and enthusiasm with which Quasimodo plays the bells

Hugo also loved bells in general. In the novel, he writes a long paean to the bells of Paris, telling his readers to imagine how they must have sounded in the time of his novel’s setting:

And if you wish to receive of the ancient city an impression with which the modern one can no longer furnish you, climb—on the morning of some grand festival, beneath the rising sun of Easter or of Pentecost — climb upon some elevated point, whence you command the entire capital; and be present at the wakening of the chimes. Behold, at a signal given from heaven, for it is the sun which gives it, all those churches quiver simultaneously. First come scattered strokes, running from one church to another, as when musicians give warning that they are about to begin. Then, all at once, behold! — for it seems at times, as though the ear also possessed a sight of its own, — behold, rising from each bell tower, something like a column of sound, a cloud of harmony. ...

Lend an ear, then, to this concert of bell towers; spread over all the murmur of half a million men, the eternal plaint of the river, the infinite breathings of the wind, the grave and distant quartette of the four forests arranged upon the hills, on the horizon, like immense stacks of organ pipes; extinguish, as in a half shade, all that is too hoarse and too shrill about the central chime, and say whether you know anything in the world more rich and joyful, more golden, more dazzling, than this tumult of bells and chimes; — than this furnace of music, — than these ten thousand brazen voices chanting simultaneously in the flutes of stone, three hundred feet high, — than this city which is no longer anything but an orchestra, — than this symphony which produces the noise of a tempest.

After the restoration of Notre Dame began in 1856, in great part due to Hugo’s novel, Napoleon III donated four new bells to celebrate his son’s baptism. Unfortunately, it soon became obvious to most hearers that the 19th century bells were cast from inferior materials and were not in tune with the old ones.

After the city suffered almost two centuries of disharmony among the bells, in 2013, in honor of the cathedral’s 850th anniversary and six years before the 2019 fire, new bells were cast to duplicate the sound of the bells that had been melted down during the era of the French revolution. The 19th century bells were originally to be melted down, but due to protests, they were preserved. In 2019, Emmanuel and the new bells survived the fire.

Emmanuel rang on Sept. 29, 2019, for the funeral of Jacques Chirac. After the new bells’ blessing on Feb. 2, 2013 — the day before Palm Sunday, opening of Holy Week — the new bells rang for the first time, this time in harmony with the bell Emmanuel. And on April 15, 2020, Emmanuel rang by itself to commemorate the first anniversary of the fire.

The twisted frustration of Archdeacon Claude Frollo

Through his character of Frollo, Hugo attacks the sincerity and celibacy of the priesthood. In Hugo’s story, Claude Frollo begins as a too-studious young man whose heart only opens when he grows to pity and adopt his little brother Jehan at the death of his parents. When Frollo comes across Quasimodo at the foundling’s cradle surrounded by people gossiping about how the monstrous child must be from the devil and should be killed, he thinks his brother might someday be in a similar position. He vows in his heart to bring up this boy for the love of his brother, so that, whatever might be in the time to come the faults of little Jehan, he might have the benefit of this charity done in his behalf.

Frollo also teaches the poor scholar Pierre Gringoire. So in the book, Frollo at least had good intentions. Some critics think Frollo goes mad because Jehan turned out to be a ne’er do well carousing student who is always lying to his brother to get more money, because Gringoire is such a fool, and because Quasimodo is barely teachable.

But the following passage shows Hugo’s view, that Frollo has been made mad and is so full of desire for Esmeralda that he arranges for her death because she refuses him — all because he is a priest and has made vows of celibacy.

He thought of the folly of eternal vows, of the vanity of chastity, science, religion, and virtue. ... And when, while thus diving into his soul, he saw how large a space nature had there prepared for the passions, he laughed still more bitterly. He stirred up from the bottom of his heart all its hatred and all its malignity; and he perceived, with the cold indifference of a physician examining a patient, that this hatred and this malignity were but vitiated love; that love, the source of every virtue in man, was transformed into horrid things in the heart of a priest, and that one so constituted as he in making himself a priest made himself a demon.

And although much of the anti-clerical fervor of Hugo’s novel is softened in the Disney movie, it features a song called “Hellfire” that is sung by Frollo — in which he plans to have Esmeralda killed if she won’t give into him — and is attributed to his sexual frustration.

What did Hugo think about the cathedral’s namesake?

Because the cathedral is named after Our Lady and was built to honor her, Hugo should have recognized her as an animating spirit of the cathedral too. But Hugo never acknowledgesd the patronage of Our Lady, and Our Lady is never mentioned except for the many oaths “by the Virgin.”

For another example, anti-royalist and anti-religionist Hugo portrays Louis XI as a cynical old capricious king whose favorite oath is “Pasque Dieu.” In modern French, Pâques means Easter, and the oath means, “by Christ’s Resurrection!” Similar swear words have been frequently used, such as “s’wounds” (“by his wounds”), and “Sacra Dieu” (“by Blessed God”). And they have morphed into meaningless equivalent so-called minced oaths: s’wounds into “zounds” and Sacra Dieu into “sacre bleu,” a meaningless term that translates as “by holy nlue.”

In a pivotal scene, Esmeralda has been condemned to death as a witch due to Frollo’s accusation, and the selfish old king believes that because the people are trying to remove Esmeralda from her sanctuary in Notre Dame, they are attacking him. The king says, “They are besieging our Lady, my good mistress, in her own cathedral! It is myself whom they are assailing. The witch is under the safeguard of the church, the church is under my safeguard. … It is myself, after all!”

The king tells his aid to “exterminate the people and hang the sorceress,” but he is reminded that Esmeralda is claiming sanctuary.

‘Pasque Dieu! sanctuary!’ ejaculated the king, rubbing his forehead. ‘And yet the witch must be hanged.’

Here, as if actuated by a sudden idea, he fell upon his knees before his chair, took off his hat, laid it upon the seat, and devoutly fixed his eyes on one of the leaden figures with which it was garnished. ‘Oh!’ he began with clasped hands, ‘my gracious patroness, our Lady of Paris, forgive me! I will do it but this once. That criminal must be punished. I assure you, Holy Virgin, my good mistress, that she is a sorceress who is not worthy of your kind protection. ... Forgive me ... Our Lady of Paris! I will never do so again, and I will give you a goodly statue of silver.’ He made the sign of the cross, rose, put on his hat.

The villainous king again sends his soldiers to “hang the sorceress,” apparently satisfied that his cynical promise of a statue of silver for violating the practice of sanctuary has reconciled Our Lady to his evil plan.

The statue of the Virgin of Paris

Our Lady is represented at least 37 times in the cathedral in the form of sculptures, paintings and stained glass. The statue called the Virgin of Paris is the most famous of them all.

This Virgin of Paris statue was carved in the middle of the 14th century for the Saint-Aignan Chapel in the former cloister of the Canons — priests who live together and pray the Divine Office — on the City Island. In 1818, the statue was transferred to Notre Dame to replace a 13th century statue of the virgin, which had stood in the pier of the portal of the virgin until it was destroyed in 1793, during the Reign of Terror.

In 1855, during the restoration of Viollet-le-Duc, the statue was moved again. Le-Duc had another statue carved and installed at the portal of the virgin, and the Virgin of Paris statue was moved to its current location — until the fire — to a spot where an altar to the virgin stood since the end of the 12th century. The statue stood in the sanctuary, on the southeast pillar of the transept. At that spot, a plaque attested — and may still attest — that the famous French author Paul Claudel was converted at Christmas Day Vespers in 1886.

After the 2019 fire, the statue was removed from Notre Dame for safekeeping. A few days later, Cardinal Robert Sarah was photographed visiting the statue where it was being kept.

The interior of the Notre Dame Cathedral on City Island in Paris, picture in 2014. Creative Commons photo by Atibordee Kongprepan

Final thoughts

Obviously, Victor Hugo had an immense love for the Notre Dame Cathedral and a great scorn for the religious beliefs that brought the cathedral into being.

It’s puzzling to me how strongly Victor Hugo loved all the Gothic churches of the Middle Ages when he despised the religion that inspired those churches. How could he not have realized the contradictions — that without the Catholic beliefs and liturgies that inspired and shaped these buildings dedicated to the worship of God, and without the celebration of the Mass that was the architectural and spiritual focus, these magnificent churches would never have existed at all?

R.T.M. Sullivan writes about sacred music, liturgy, art, literature and whatever strikes her Catholic imagination. She has published many essays, interviews, reviews and memoir pieces in print and online publications, such as Dappled Things Quarterly of Ideas, Art and Faith; Sacred Music Journal; Latin Mass Magazine; National Catholic Register; New Liturgical Movement; and Homiletic and Pastoral Review.